Bilibili & Cie v. AI-Generated Content

Content Creators are worried about their creations being stolen to create AIGC. To curb this phenomenon, Chinese Lawmakers have enacted a series of measures.

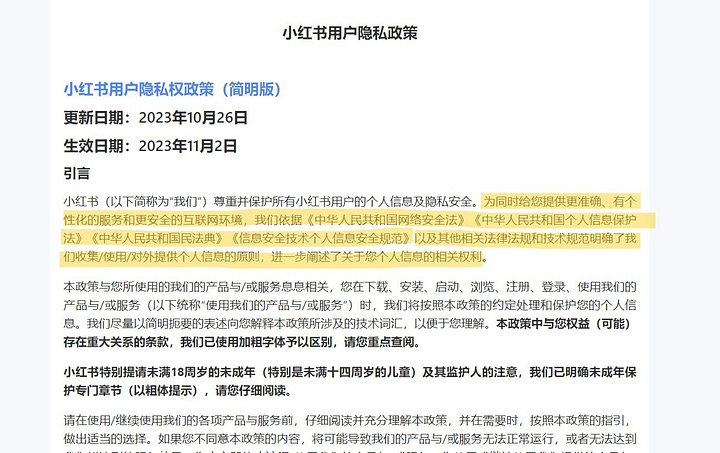

Left: Douyin has introduced a watermark and data definition speci-fications to facilitate the identification of AI-generated content. Right: Xiaohongshu ‘clarified its principles for collecting, using, and providing personal information externally, aligning with Cybersecurity Law, the Personal Information Security Specification for Information Security Technology, and other pertinent laws, regulations, and tech-nical specifications’. Screenshots are available for reference only.Description: A growing number of Content Creators are worried about their creations being stolen by generative AI (GenAI) to create content virtually indistinguishable for the average Joe from truly human-made artistic creations. In order to curb this phenomenon, Chinese Lawmakers & Mobile app regulators implemented a series of measures. In the wake of significant advancements in GenAI and widespread emergence of AI-generated content (such as DALL-E, Midjourney, RunwayML …), coupled with the increased accessibility of its use facilitated by OpenAI’s launch of its ChatGPT in 2022, Chinese social platform regulators have introduced several provisions to oversee cyberspace in relation to intellectual property and data protection breaches. Bilibili, a video-sharing website founded in June 2009 boasting around 350 million users, has become the latest social platform to enforce stringent regulations regarding AI-generated content (AIGC).

Bilibili v. Abusive use of GenAI

Bilibili’s heightened scrutiny of AI-generated content aligns with a notable increase in copyright and data protection breaches. Users also express concerns that AI-generated videos could potentially overshadow human-made content, leading to widespread deception. In response to these concerns, there has been a push for more stringent penalties and rigorous monitoring for undisclosed AIGC to mitigate the potential risks associated with its proliferation on social media platforms.

Content Creators, social platforms & generative AI

Bilibili’s new regulations represent the latest in a series of efforts by Chinese platforms to restrict the use of GenAI for content creation.

ByteDance’s popular short-videos sharing app, Douyin (Tiktok), took decisive action earlier this year, as reported by Sixth Tone. These measures include mandating Content Creators to prominently label the use of AI-generated content (对人工智能生成内容进行显著标识), requiring ID verification for users employing digital avatars (虚拟人技术使用者需实名认证), and holding creators accountable (后果负责) for the misuse of AI technologies in compliance with new legal provisions (refer to Section II. A for a timeline and background on China’s enacted AI/Cyberspace monitoring-related laws).

In an official Weixin (WeChat) post, Douyin reaffirmed its commitment to

1) Fully protect individual's rights and interests (尊重并充分保障个人权益)

2) Combat production, dissemination of fake news (避免虚假信息的生产传播)

3) Actively addressing knowingly spread rumors (造谣传谣的内容)

4) Preventing the publication of infringing content (发布侵权内容)Douyin has also pledged to collect users’ feedback on generated content, using it to refine its AI-centered strategies and policies.

To tell the truth, a number of Chinese users are expressing skepticism regar-ding GenAI-based applications and their ability to safeguard their rights. In the last few months, for instance, a viral AI-driven photo app called Miaoya Camera (妙鸭相机), a WeChat-integrated program known for creating perso-nalized and artistic portraits, has caught the attention of Tech regulators.

Concerns arose this summer over the app’s seemingly unrestrained external use of personal data gathered for training AI models. In response to the esca-lating concerns, Miaoya released an update, contending that the original content agreement was inaccurate (原协议内容有误).

The developers of Miaoya emphasized their unwavering commitment to pro-tecting users’ privacy and legitimate rights and interests (始终注意保护用户隐私和正当权益). Furthermore, they assured users that the collected photos would not be misused for any other purposes and would be automatically deleted (自动删除) once the personalized portrait is generated.

The impact of AI-generated images extends to users’ confidence in popular lifestyle apps, including Xiaohongshu (小红书), where the incorporation of AI technology is a relatively recent development. Xiaohongshu’s AI pictures generator, Trik AI, and another AI tool, Ci Ke, which generates images from text, have recently been embroiled in various controversies.

Accusations have surfaced, suggesting the unlawful utilization of some illustrators’ creations to train their programs, sparking widespread backlash among Xiaohongshu’s users. This discontent has culminated in a number of boycotts against the platform.Tightening Rules

The misuse of AI has raised a new set of concerns among Bilibili’s Content Creators, prompting the platform to introduce fresh guidelines and implement stricter rules not previously in place.

In response, Bilibili has rolled out a ‘labeling system,’ urging content creators to include (添加内容标识) a relevant tag that categorizes their video. Among these categories, ‘AI-generated content’ is emphasized to prevent potential misunderstandings.

The following priority order should be observed: artificial intelligence synthesis technology > dangerous behavior > rational and moderate consumption > causing discomfort > personal views > for entertainment purposes only

(人工智能合成技术>危险行为>理性适度消费>引人不适>个人观点>仅供娱乐).

In an official announcement titled “Actively Adding Content Identification (关于“主动添加内容标识”的公告)”, Bilibili’s regulators have stipulated that when publishing content containing AIGC authors must include a statement speci-fying that the video utilizes artificial intelligence synthesis technology to prevent any potential misinformation of the audience (发布包含人工智能生成的内容AIGC时,请添加作者声明:该视频使用人工智能合成技术。避免误导观众).

Similarly, specific provisions have been established for gambling, high-risk, and distressing content, requiring users to add relevant tags to their videos accordingly. In the event of erroneous labeling, the platform reserves the right to modify the provided label.

A top-down process with more advantages than drawbacks

Douyin and Bilibili’s newly published top-down regulations are reminiscent of China’s vertical governance.

Matt Sheehan1, an Asia Program fellow at Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, talking for Stanford’s DigiChina2, argues that is

China’s fundamental difference with the West’s approach to AI regulations:

‘[in] rolling out its earlier regulations on recommendation algorithms and “deep synthesis,” the CAC took a “vertical” approach to regulating AI: Each regulation targeted a specific AI application, or set of applications. This contrasts with the more “horizontal” regulatory approach in the European Union’s AI Act, which covers most applications of the technology’.

Sheehan further explains that China’s approach to AI regulations is charac-terized by its precision and detail. As China continues to advance and refine its AI capabilities, Sheehan suggests that the country may be better positio-ned to expedite much-needed updates to AI regulations.

Notably, the recent AI regulations imposed by the latest social platforms align with the 2021 Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL), serving as China’s equivalent to the GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation) in Europe. This alignment is motivated by a desire to avoid encountering similar challenges as CNKI did experience, emphasizing the importance of complying with robust data protection laws on both sides.

Chinese-style regulations

The Big Picture: Setting the limits of AI

Douyin, Xiaohongshu & Bibilibi’s AI-related guidelines function as practical measures aligning with the overarching legal provisions established by China’s state regulatory authorities. These guidelines play a crucial role in shaping and overseeing the development of AI.

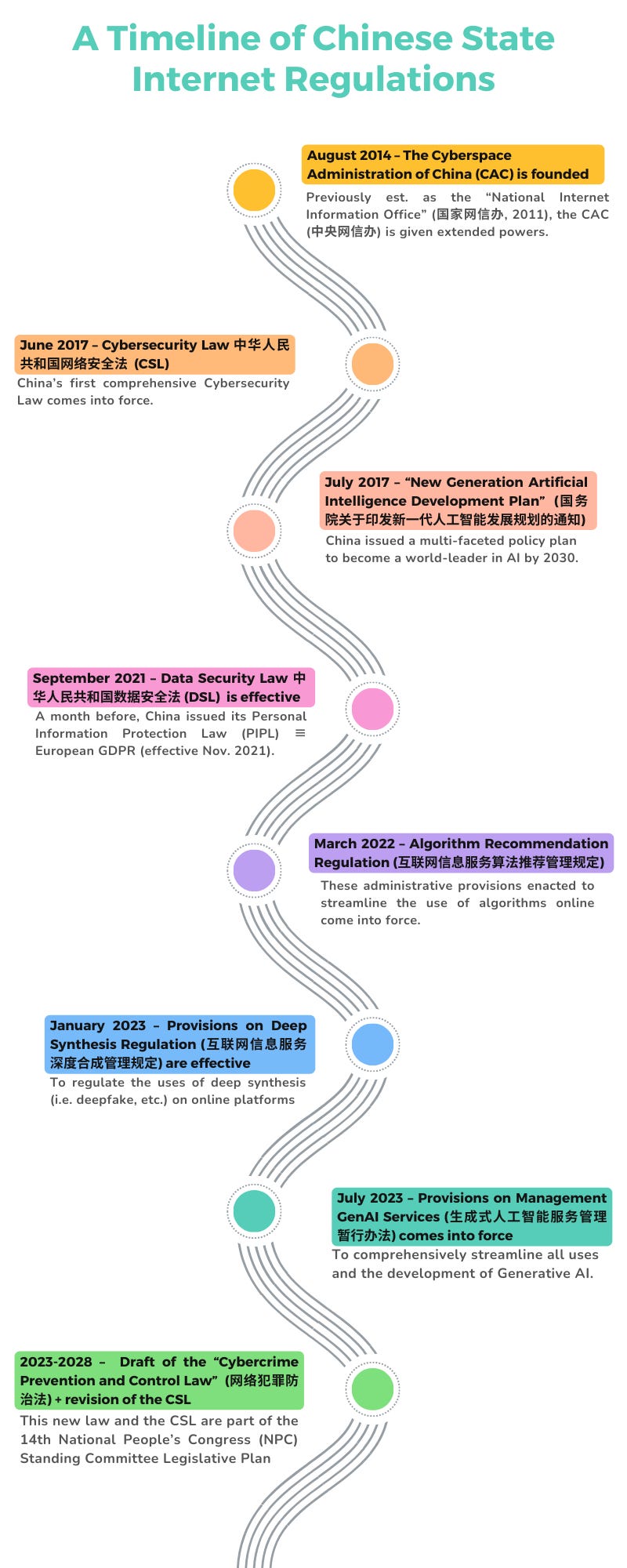

Over the past few years, the State Council and the National People’s Congress of China have formulated several foundational legal provisions, serving as guiding principles for the creation of detailed and specific AI-related laws.

Notably, China implemented its first comprehensive

a) Cybersecurity Law (中华人民共和国网络安全法, CSL) in June 2017, followed a month later by a policy paper

b) “New Generation Artificial Intelligence Development Plan” (国务院关于印发新一代人工智能发展规划的通知) introduced with the aim of positioning China as the world leader in AI by 2030 (English translation / Original)

c) Data Security Law (中华人民共和国数据安全法 (DSL)) in September 2021, serving as a partial counterpart to the EU’s Digital Services Act.

Several specific provisions pertaining to the development of AI have been meticulously edited, revised, passed by the National People’s Congress (NPC), and subsequently implemented at the national level. These include 4 key regulatory texts:

a) Administrative Provisions on Algorithm Recommendation for Internet Information Services 互联网信息服务算法推荐管理规定 (abbreviated as Algorithm Recommendation Regulation, 简称 “算法推荐规定”) enforced March 2022, address the use of algorithms targeting user preferences.

b) Provisions on Management of Deep Synthesis in Internet Information Service 互联网信息服务深度合成管理规定 (Deep Synthesis Regulation “深度合成规定”), implemented in January 2023, address the deployment of deep synthesis technologies (a term popularized by Tencent to describe a subset of gen-AI technologies) by internet information services in China.

c) Provisions on Management of Generative Artificial Intelligence Services 生成式人工智能服务管理暂行办法 (Generative AI Regulation “生成式AI办法”), in effect since August 2023, aim to oversee the development and usage of all generative AI technologies providing services in China.

d) Finally, a more specific provision related to AI research and development (R&D), the Trial Measures for Ethical Review of Science and Technology Activities 科技伦理审查办法 (草案) was published for public comments in April 2023 [English / Original].

If these legal provisions differ both in degree and kind, as emphasized by Matt Sheehan in his paper for Carnegie, he underscores the significance of ‘information control’ as a central objective of the Algorithm Recommendation Regulation, Deep Synthesis Regulation, and Generative AI Regulation. All three regulations mandate developers to submit filings to China’s algorithm registry (算法备案系统), a recently established government repository designed to collect information on the training of algorithms.

The three aforementioned provisions outline a broad spectrum of obligations, encompassing: 1] Security Assessment: Online platforms, under certain conditions, are required to submit a security assessment report to the local city-level cyberspace administration and public security authority before launching their products, services, applications, functions, or tools. This security assessment stands distinct and independent from the CAC security assessment mandated under the Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL) for the export of personal data, as well as the algorithm self-assessment report (integral to the algorithm filing) (see. Latham & Watkins3).

2] Ethical Review: Entities such as scientific clusters, research institutions, universities, and private companies involved in “ethically sensitive” science and technology activities, particularly in areas like AI, must establish a science and technology ethical review committee.

3] Fact-Checking: AI algorithms must not be employed to disseminate fake news or illegal information. In cases where such information is identified, platforms are obligated to promptly cease transmission, delete the content, and report the incident to local CAC counterparts or other relevant government authorities.

4] Labeling Content: The Deep Synthesis Regulation, Article 17, mandates the labeling of content that may cause confusion or mislead the public (可能导致公众混淆或者误认的) as deep synthetic content. This includes intelligent conversation or writing that simulates the style of a real person (e.g. ChatGPT), voice simulations, face image synthesis and manipulation, generation or editing services such as immersive simulation scenes, and services capable of producing deepfakes.

5] Public Disclosure: Platforms are required to clearly notify users about the use of algorithmic recommendations. Platforms are prohibited from establishing algorithm models that induce user addiction or over-consumption (不得设置诱导用户沉迷、过度消费), in accordance with Article 8 of the Algorithm Recommendation Regulation.

AI-related services and products must adhere to compliance laws and guiding principles, including the Cybersecurity Law (CSL), Data Security Law (DSL), Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL), and the Science and Technology Progress Act (STPA), as explicitly outlined in Article 4 of the Algorithm Recommendation Regulation, Deep Synthesis Regulation, and Generative AI Regulation. Moreover, there is an ongoing effort to introduce a National AI Law as of December 2023. The State Council of China has initiated the drafting of a comprehensive Artificial Intelligence Law (人工智能法), is anticipated to be presented to the National People’s Congress.

There are even more specific measures at the provincial level, exemplified by the Beijing Municipal Health Commission’s drafting of new rules. These rules are designed to rigorously prohibit the use of AI for the automatic generation of medical prescriptions. The objective is to uphold the principle that human medical professionals retain responsibility for prescribing medications. This underscores the commitment to maintaining a human-centric approach in medical decision-making and treatment procedures.

Empowering AI by providing a clear legal framework

All of these regulatory initiatives might lead Chinese AI users to perceive that the State Council and the NPC are actively working to regulate the use of AI algorithms and tools online, possibly with an inclination toward restricting or even prohibiting certain AI-related services, but within well-defined parameters. Angela Huyue Zhang, a Global Professor of Law at NYU Law School, Associate Professor of Law at HKU, and Director of the Philip K. H. Wong Centre for Chinese Law, who is also the author of Chinese Antitrust Exceptionalism (Oxford University Press), provides valuable insights.

According to Zhang, there is no ‘reason to think that the CAC would seek to create unnecessary roadblocks: just two weeks after the interim measures [on Generative AI] went into effect, the agency gave the green light to eight companies, including Baidu and SenseTime, to launch their chatbots’. Another crucial aspect of these legal provisions is their encouragement of collaboration among major stakeholders in the AI supply chain. This reflects a recognition that technological innovation ‘relies on effective exchanges between government, industry, and academia’. Professor Zhang emphasizes that, in this context, Chinese regulators play a role as enablers rather than impediments to the development of Chinese AI giants.

Similarly, international legal regulation of AI is a focal point for lawmakers worldwide. As highlighted by the late Kissinger, global collaboration in the field of AI is paramount, especially in the face of escalating geopolitical risks. While geopolitical imperatives such as the US-China tech competition may advocate for an industrial-centered de-risking strategy, it is crucial not to sideline the potential for cooperation between the United States and China in the field of AI. Unlike a ‘risk-based approach’ akin to the EU’s AI regulatory regime, which emphasizes caution, Bird & Bird’s paper4 suggests that Chinese regulators adopt a different stance. They focus more on striking a balance between industry development and regulation, rather than solely restraining the technology. This is evident in the emphasis on China’s innovative-driven approach to AI, as articulated in Articles 5 and 6 of the Generative AI Measures, aligning with the technological agenda established by the 2017 New Generation Artificial Intelligence Development Plan.

Bilibili’s implemented measures and the broader legal framework in China exhibit a distinctive Chinese-style governance approach, characterized by comprehensive guiding principles, a mix of administrative provisions strictly prohibiting certain elements, and corporate regulations that align with a politically-driven agenda. Zac Haluza, speaking to DigiChina and discussing drafts of the Generative AI measures, underscores the critical importance of considering the state’s current priorities. These priorities include an emphasis on increased digitalization, achieving self-sufficiency in science and technology, and fostering innovation within private enterprises:

‘With these guidelines also requiring AIGC product developers to document the entire lifecycle of their products, China can (at least in theory) feel more at ease as it aims to ramp up the development of AI that could drive its digital development’.

That does not mean, however, that the concept of AI governance with Chinese characteristics (中国特色AI治理) is cynical, merely political, or solely growth-driven. Article 1 of the Generative AI Measures explicitly emphasizes the objective of promoting the healthy development and regulated application of Generative AI (为了促进生成式人工智能健康发展和规范应用). Moreover, Article 4 underscores the importance of respecting social morality and ethical ethics in the deployment of AI technologies (尊重社会公德和伦理道德), and the inclusion of considerations for intellectual property protection and individuals’ legitimate rights further demonstrates a nuanced and multifaceted approach to AI governance. All things considered, these provisions highlight a broader commitment to responsible AI development, considering not only economic and political objectives but also ethical considerations and societal interests.

Matt Sheehan, ‘China’s AI Regulations and How They Get Made’, July 10, 2023, Carnegie Endowment https://carnegieendowment.org/2023/07/10/china-s-ai-regulations-and-how-they-get-made-pub-90117

DigiChina, Stanford Cyber Policy Center, FSI, ‘How will China’s Generative AI Regulations Shape the Future? DigiChina Forum’, April 19, 2023. Link ︎

Latham & Watkins’ Client Alert Commentary, ‘China’s New AI Regulations’, August 16, 2023. English version / 中文版

Bird & Bird, ‘What You Need to Know About China’s New Generative AI Measures’, August 3, 2023. https://www.twobirds.com/en/insights/2023/china/what-you-need-to-know-about-china%E2%80%99s-new-generative-ai-measures